An introduction to event data modeling

Data modeling is an essential step in the Snowplow data pipeline. We find that those companies that are most successful at using Snowplow data are those that actively develop their event data models: progressively pushing more and more Snowplow data throughout their organizations so that marketers, product managers, merchandising and editorial teams can use the data to inform and drive decision making.

‘Event data modeling’ is a very new discipline and as a result, there’s not a lot of literature out there to help analysts and data scientists getting started modeling event data. This blog post is a first step to addressing that lack. In it, we’ll explain what event data modeling is, and give enough of an overview that it should start to become clear why it is so important, and why it is not straightforward.

1. So what is event data modeling?

Let’s start with a definition:

Event data modeling is the process of using business logic to aggregate over event-level data to produce 'modeled' data that is simpler for querying.

Let’s pick out the different elements packed into the above definition:

a. Business logic

The event stream that Snowplow delivers is an unopinionated data sets. When we record a page view event, for example, we aim to record it as faithfully as possible:

- What was the URL that was viewed?

- What was the title?

- Is there any metadata about the page contents that we can capture?

- What was the cookie ID of the user that loaded the web page?

- On what browser was the user?

- On what device?

- On what operating system?

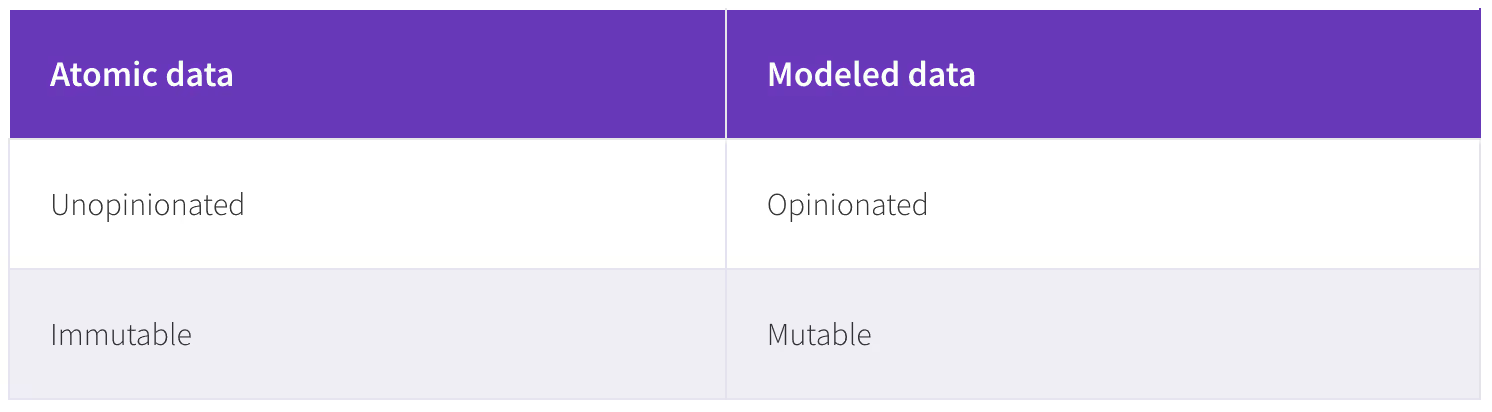

All of the above data points would be recorded with the event. None of the above data points are contentious: there is nothing that would happen in the future that would change the values that we’d assign those dimensions. For clarity, we call this data ‘atomic’ data. It is event-level and it is unopinionated.

When we do event data modeling, we use business logic to add meaning to the atomic data. We might look at the data and decide that the page view recorded above was the first page in a new session, or the first step in a purchase funnel. We might infer from the cookie ID recorded to who the actual user is. We might look at the data point in the context of other data points recorded with the same cookie ID, and infer an intention on the part of the user (e.g. that she was searching for a particular product) or infer something more general about the user (e.g. that she has an interest in French literature).

These inferences are made based on an understanding of the business and product. That understanding is something that continually evolves. As we change our business logic, we change our data models. That means that the modeled data that is produced by the process of event data modeling is mutable: it is always possible that some new data coming in, or an update to our business logic, will change the way we understand a particular event that occurred in the past.

This is in stark contract to the event stream that is the input of the data modeling process: this is an immutable record of what has happened. The immutable record will grow over time as we record new events, but the events that have already been recorded will not change, because the different data points that are captured with each event are not contentious. It is only the way that we interpret them that might, and this will only impact the modeled data, not the atomic data.

We therefore have two different data sets, both of which represent “what has happened”:

b. Aggregation

When we’re doing event data modeling, we’re typically aggregating over our event level data. Whereas each line of event-level data represents a single event, each line of modeled data represents a higher order entity e.g. a workflow or a session, that is itself composed of a sequence of events. We’ll give concrete examples of these higher order entities below.

Note that this is not always the case: sometimes we may want our modeled data to be event level. In that case the modeled data will look like the atomic data, but have additional fields that describe those infered.

c. Simple to query

The point of data modeling is to produce a data set that is easy for different data consumers to work with. Typically, this data will be socialized across the business using a business intelligence tool. That puts particular requirements on the structure of the modeled data: namely that it is in a format suitable for slicing and dicing different dimensions and measures against one another. In general, atomic data is not suitable for ingesting directly in a business intelligence tool. (This is only possible where those tools support doing the data modeling internally.)

2. Why in most cases, simply aggregating over event data is not enough

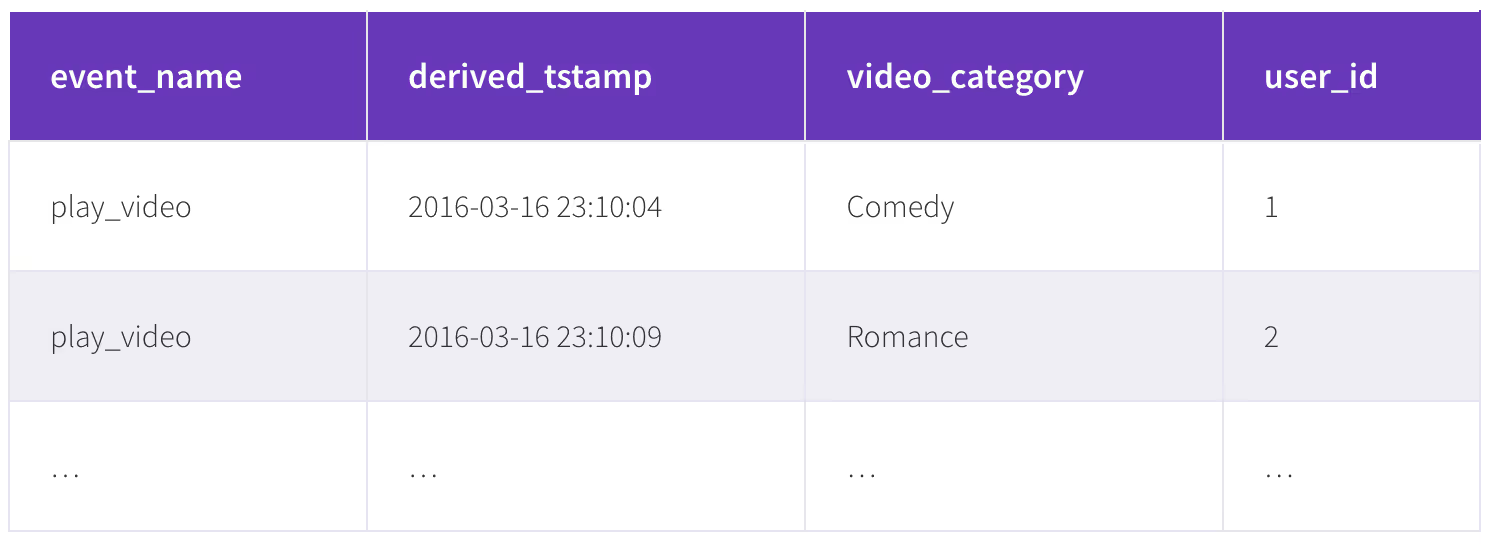

Sometimes when we analyze event data, we only need to perform simple aggregations over atomic data. For example, if we track an event play_video and for each of those event track the category of video played, we may want to compare the number of videos played by category by day, to see if particular categories are becoming more popular, perhaps at the expense of others. This data set might look like the following:

It would be straightforward to perform the aggregation on the atomic data delivered by Snowplow using a query like the following:

select date_trunc('day, derived_tstamp'), video_category, count(*) from atomic.events where event_name = 'video_play' group by 1,2 order by 1,2

Most of the time, however, performing simple aggregations like the one above is not enough. Often, we’re interested in answering more complicated questions than which is the most popular video category. Questions like:

- How do conversion rates vary by acquisition channel?

- What point in the purchase funnel to most users churn? Does that vary by user type?

The above two questions require more than simple aggregations. If we want to compare conversion rates by acquisition channel, we have to take an event early on in a user journey (the user engaged with a marketing channel) and tie that to an event that may or may not occur later on in the same user’s journey (the user converted). Only then do we aggregate over users (calculate the % of users converted) and slice that by channels (calculate the % of users converted by each channel) rather than simply aggregating over the underlying marketing touch and conversion events. To recap the computational steps required, we need to:

- Group events by users

- For each user, identify an acquisition channel

- For each user, identify whether or not they converted

- Aggregate over users by acquisititon channel, and for each channel calculate an aggregated conversion rate

- Compare the conversion rate by channel

The second example is similar: again we need to aggregate events by users. For each user we identify all the events that describe how they engaged with a particular funnel. For each user we then categorize how far through the funnel they get / where in the funnel they ‘drop off’, based on the event stream. We then aggregate by user, slicing by user type and stage in the funnel that each user drops off, to compare drop off rates by stage by user type.

As should be clear in both the above examples, when we’re dealing with event data, we’re generally interested in understanding the journeys that are composed of series of events. Therefore, we need to aggregate events over those journeys to generate tables that represent higher order units of analysis like funnels or workflows or sessions.

We’re often interested in understanding the sequence of events, and how impact events earlier on in a user journey have on the likelihood of particular events later on in those same user journeys. Understanding that sequence is not something that falls out of a standard set of aggregations functions like COUNT, SUM, MAX. That can make modeling event data difficult, because it is not trivial to express the business logic that we wish to apply to event level data in languages like SQL that have not been built around event data modeling.

3. Different higher-order units of analysis

There are a number of different units of analysis that we can produce with our event data model:

- Macro events

- Workflows / units of work

- Sessions

- Users

- Tying particular classes of events in a user journey together to understand the impact of earlier events on later events

Let’s look at each in turn:

a. Modeling macro events from micro events (e.g. video views)

‘Macro events’ are made up of micro events. For example, if we are a video media company, we may want to understand how individual users interact with individual items of video content. An example event stream for a particular user / video content item might look like this:

In the example above we have modeled an event stream that describes all the micro-interactions that a user has with a particular video into a summary table that records one line of data for each video each user has watched. Note how the summary table includes:

- Information about the viewer (notably the user ID). This means we can easily compare consumption patterns between different user types.

- Information about the video (notably the video ID). This means we can easily compare consumption patterns by different video types.

- Information summarizing the user-video interaction i.e. has the user completed the video, has the user shared the video?

This summary table is much easier to consume that the event stream on the left: we can perform simple group by and aggregations functions on it to e.g. compare viewing figures or engagement rates by user types and video types.

b. Modeling workflows / units of work e.g. sign up funnels, purchase funnels

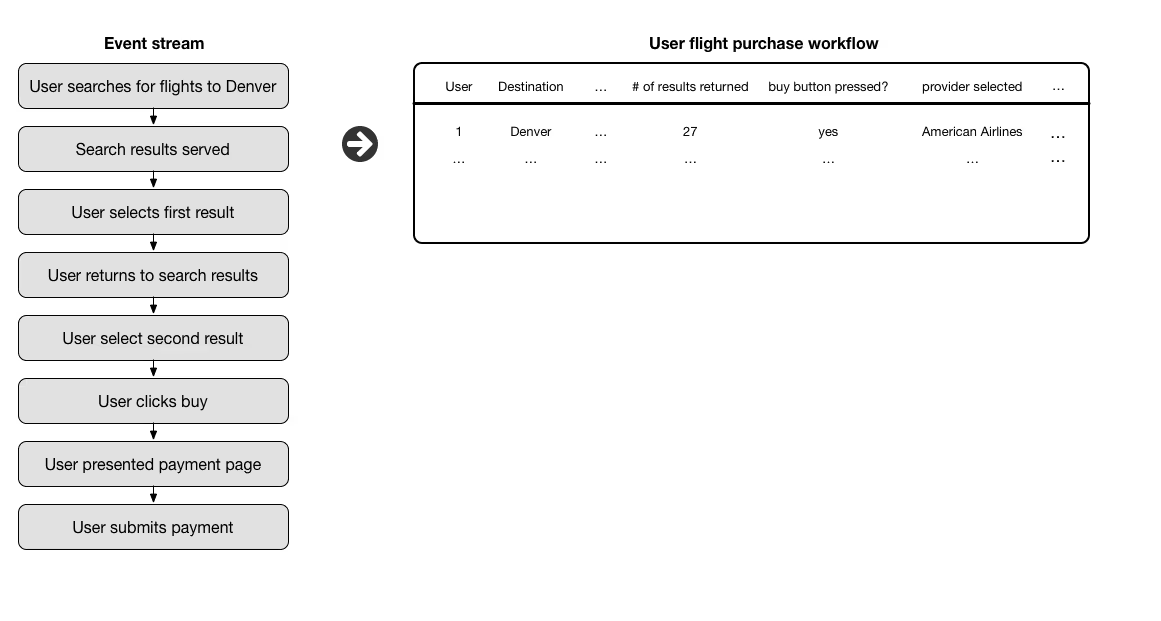

Often we are interested in understanding the sequence of events that represent the way a user interacts with a particular workflow or works towards a defined goal. An example is illustrated below of a user interacting with a travel site:

Our summary table aggregates the event-level data down to an individual workflow level, where each workflow represents the journey that starts with a user performing a search, and ends when that user:

- Makes a purchase of one of the search results, or

- performs another search, or

- drops out altogether.

Our aggregated data table contains a lot of interesting data, including:

- Data about the initial search that was performed. This is data that will be fetched from the early events in the workflow.

- Data about the actual results that the user interacts with: which results were selected, where were they ranked in the results.

- Which result (if any) the user selected and went on to buy. This data will be taken from later events in the workflow

Again, note how the modeled data should be easy to work with: we can easily:

- Compare the number of searches to different destinations

- Compare conversion rates by destination

- Explore whether higher ranking results are more likely to be selected and then purchased, and see how this varies by user type, location and other key data pionts

c. Modeling sessions

It is very common in digital analytics to group sequences of events up into ‘sessions’ and then aggregate data by session. Typical aggregations will include data on:

- How the user was acquired.

- Where the session started (e.g. the ‘landing page’).

- How long the session lasted.

- What was the session worth. (Did a transaction occur? How much ad revenue was made? Were any conversion events recorded?)

- What was the user trying to accomplish in the session.

Sessions are meant to represent continuous streams of user

activity. In web, it is common to define a session as ending when a period of 30 minutes passes and no event takes place.

At Snowplow we are not big fans of the ‘session’ concept: often the definition of what constitutes a session is opaque, and even when it is clearly defined, it often does not correspond to a meaningful unit of work from a user’s experience: a definition based on a 30 minute timeout made sense in the late 1990s when users would interact with one website at a time, but makes much less sense in a multi-screen, multi-tab world, where users might be engaged with several tasks simultaneously.

Nonetheless, the idea of dividing user activity into discrete blocks of continuous activity is a very useful one. In general we prefer grouping events around specific end goals (i.e. workflows or ‘units of work’) as described above. In spite of our reservations, many people (including many of our users) still sessionize their data.

An interesting alternative to sessions, common amongst mobile games companies, is to aggregate data by user by day. (This gives rise to the famous ‘daily active user’ metric.)

d. Modeling users

A lot of useful user-level data can be gleaned by aggregating over a user’s entire event stream. For example, based on that entire history, we might:

- Bucket users into different cohorts based on when they were acquired or how they were originally acquired.

- Categorize users into different behavioral segments.

- Calculate actual and predicted lifetime value for individual users based on their behavior to date.

e. Tying particular classes of events in a user journey together to understand the impact of earlier events on later events

In all the above examples we were combining series of events that occur for individual users and grouping them in ways that summarize continuous streams of activities, where those streams were:

- Macro events

- Workflows

- Sessions

- Complete user journeys

Often however, we are particularly interested in specific classes of events and want to understand the impact that one class of events has on the likelihood of another class of event later on in a user’s journey, regardless of what other events have happened in between.

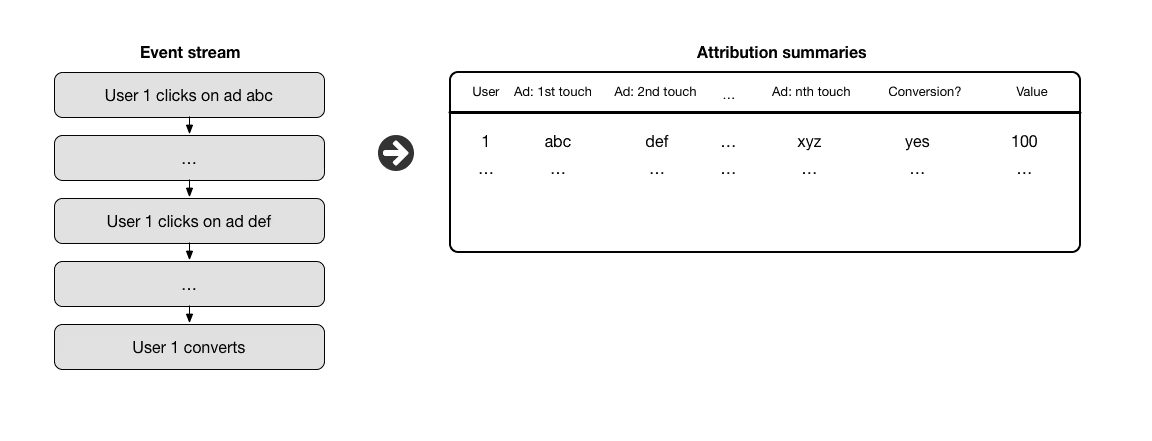

A common example of this type of analysis is attribution modeling. There is a large set of attribution models that are fed with data that describes:

- What marketing channels a user has interacted with (first class of events, early on in a user’s journey), with

- Whether or not a user subsequently converted (second class of events, that occur later on in a user’s journey.)

This type of data modeling is illustrated below:

There are a number of ways we can model attribution data. Many approaches require data in the format shown above: where we aggregate a continuous stream of user activity from a first marketing touch forwards, including any details about any subsequent marketing touches and conversion events. Once the data has been aggregated as above, it is generally straightforward to:

- ‘Measure’ the impact of an marketing channel on the likelihood that a user converts. (E.g. by comparing conversion rates for users who’ve only interacted with ad

abcwith those who have interacted with addefto see what the incremental impact of interacting withdefis on the conversion rate.) - Apply an attribution model (i.e. credit the different marketing touches upstream of a conversion with the value of the downstream conversion) and perform analysis

4. Characteristics of modeled data

Now that we’ve seen some examples of higher order entities that are outputed as part of the event data modeling process, we can draw some observations of the modeled data relative to the atomic data:

- It is typically lower volume (fewer rows of data). While it is possible to output modeled event-level data, in practice it is more common to output aggregated data. This data set is smaller than the event level data set, so faster to query.

- There are typically more columns in the modeled data set. When we apply business logic to the underlying event level data, we typically generate new ways of classifying our different higher order entities. To take the example of users, we might come up with multiple ways to classify our users based on their behaviors. Similarly, we might have a large number of different fields that describe a macro event. Over time we develop new ways of categorizing entities, resulting in additional columns in our modeled data tables as we come up with new ways of slicing and dicing our data.

5. Working with modeled data

Hopefully it should be clear from the above that modeled data is much easier to work with than immutable / atomic data. The hard work of unpicking the sequence of events and applying business logic and using that to perform complex aggregations over the event-level data has already been done, delivering a data set that is easy to work with. To use the modeled data for analysis, only simple types of aggregation over our higher level entities (macro events, workflows, sessions and users) is required.

It is worth noting that for most analyses we are not working with just one modeled data set: we typically join two or more together. It is, for example, very common to join our user table with any of the other tables, to slice some metric that we’re examining by user type.

Want to see more?

This was the first in a series of blog posts and recipes on event data modeling. Get in touch if you'd like to see more and learn about our dbt data models.