Building an event grammar - understanding context

Here at Snowplow we recently added a new feature called “custom contexts” to our JavaScript Tracker (although not yet into our Enrichment process or Storage targets).

To accompany the feature release we published a User Guide for Custom Contexts - a practical, hands-on guide to populating custom contexts from JavaScript. We want to now follow this up with a post on the underlying theory of event context: what it is, how it is generated and why it is so useful for analytics. “Event context” isn’t a phrase widely used in the analytics industry - and you have to go back to our blog post Towards Universal Event Analytics for our first description of it:

Context. Not a grammatical term, but we will use context to describe the phrases of time, manner, place and so on which provide additional information about the action being performed: “I posted the letter on Tuesday from Boston“

This was a good start but there is much more to be said about event context. In this blog post, we will cover the theory of event context, grounding it in some examples of context being collected or derived by Snowplow today. I’ll then look at some ideas around sources of context, followed by some notes on the relationship between context and prepositional objects. Finally I’ll conclude with some thoughts on why event context is so powerful for analytics:

- Event context: the theory

- Context and Snowplow today

- Sources of context

- One man’s context…

- The power of context

Event context: the theory

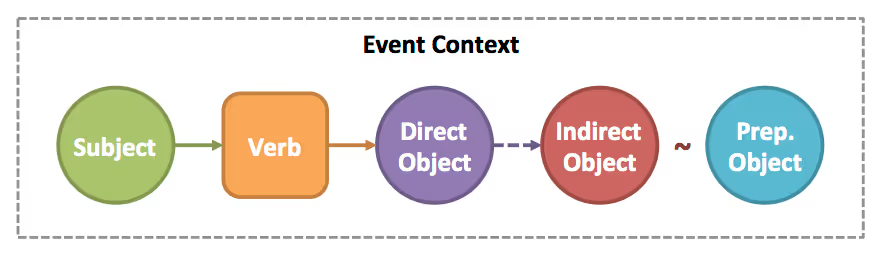

In our earlier blog post, Towards Universal Event Analytics, event context was a little crowded out by the entities (subjects and objects) and verbs which composed our event grammar:

Compared to the colourful entities and verbs, event context looked like simply “the intangible everything else” - the amorphous whitespace around our core event. Nothing could be further from the truth - event context is in fact tangible, easily recorded and hugely valuable for analysis.

Simply put, event context describes the environment and manner in which an event took place. There are strong parallels between our view of event context and the adverbial concept of “time, manner, place” used in human language to describe events. Context is used to describe, among other things:

- Where an event took place - where in the physical world, or in which digital environment

- When an event took place - either in absolute terms or relative to other events

- How an event took place - in what manner did an event take place

In fact a large proportion of Snowplow’s existing Canonical Event Model is describing the context of the given event - as we will explore in the next section.

Context and Snowplow today

Today, our Canonical Event Model contains 98 fields, and by our reckoning 57 of those fields solely relate to event context in one form or another. Here is a brief summary of the context already present:

Context categoryExample fieldsDescriptionTemporal

- dvce_tstamp

- collector_tstamp

- os_timezone

When this event took placeGeographical

- geo_latitude

- geo_longitude

- geo_country

Where in the real-world this event took placeEnvironmental

- platform

- br_name

- os_family

The computing environment in which this event took placeNarratorial

- v_tracker

- v_collector

- v_etl

Who narrated this event (our data pipeline)Antecedental

- refr_urlpath

- mkt_medium

- mkt_campaign

What occurred prior to (and potentially caused) this event

As you can see, our Canonical Event Model is chock full of context! But not all of this context is created equal - in the next section we will explore where context comes from, and how reliable it is.

Sources of context

It might be natural to assume that all event context is captured at the point of creating (“tracking” in Snowplow language) an event. In fact things are not that simple - but we can think of context coming from three distinct sources:

- Primary context: context which was captured directly at the point of creating the event

- Secondary context: context can be captured further down the event pipeline, for example at the point of collecting the event

- Derived context: new context can be derived from existing primary or secondary context

To dive into a couple of examples:

Primary and secondary timestamps

For a simple comparison between primary and secondary context, consider our two event timestamps:

Both of these are pieces of temporal context, but they originate from different places. And interestingly, they have very different reliability profiles and thus use-cases:

dvce_tstampis set by the client’s system clock, which is frequently incorrectcollector_tstampis set by the collector’s server clock, which is accurate but can only record when the event was collected, not created

Thus for absolute analyses across multiple users, collector_tstamp provides the best temporal information. However, this introduces some uncertainty around the ordering of events which happened close together, so for e.g. a funnel analysis tied to a specific user, dvce_tstamp would be the best temporal context.

Derived geographical and meteorological context

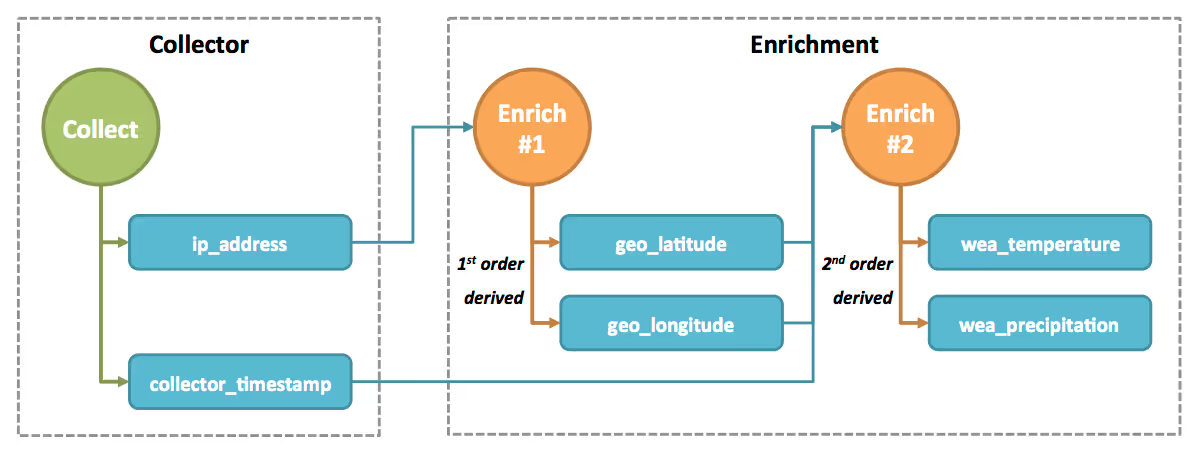

Additionally, it is possible to derive new context from one or more pieces of existing context. Here is an illustration of this:

As you can see here, we collect ip_address and collector_tstamp as pieces of secondary context in the collector. Then in the Enrichment phase, we are able to derive a new set of geographical context (geo_latitude, geo_longitude etc) by performing a MaxMind geo-IP lookup on the user’s ip_address.

To push this example further: we could potentially then use the collector_tstamp, geo_latitude and geo_longitude to derive weather context from that infor

mation. This is not an Enrichment currently supported by Snowplow, but it is a great example of a second-order derived context.

One man's context...

There’s one more complexity I’d like to discuss before wrapping up, which could be summed up by:

One event’s context is another event’s object (or subject or…)

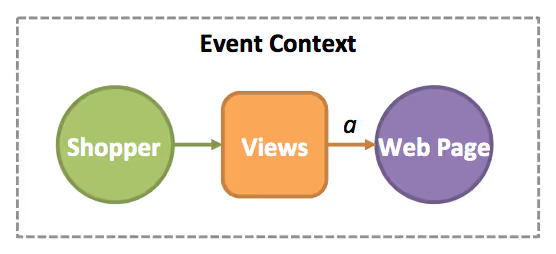

Let’s demonstrate this by comparing two events. In the first, a customer is viewing a web page:

In the second event, the customer is now adding an item to their basket:

But crucially, in the second event, the customer is still on a web page. This web page is no longer the direct object of the event - but it is still relevant information: it gives us spatial context, on where the event took place.

Thus we can see that one event’s direct object becomes context for another event; in both events, we are modelling some kind of web_page entity, but it serves different roles in both events.

We introduced a closely-related concept in our blog post Towards Universal Event Analytics with talk of prepositional objects:

the first player (Subject) kills (Verb) the second player (Direct Object) using a nailgun (Prepositional Object)

As we evolve our event grammar further, we will need to consider whether prepositional objects and context should be treated separately, or merged into one broader concept.

The power of context

Event context provides a huge amount of valuable metadata around our core subject-verb-object grammar, as evidenced by the large proportion of our Canonical Event Model which is given over to context.

If the core subject-verb-object dynamic tells us who did what to whom, then context tells us something much more discursive and subjective, but much richer too: how was it done, where was it done, why was it done. We are hugely excited about all forms of context at Snowplow, and we believe there is much more context still to be collected, not least:

- Tracking additional primary context from new platforms and environments, such as iOS or Android-specific environmental context

- Capturing additional secondary context from our collectors, for example capturing browser cookies or other headers

- Generating new derived context in our Enrichment process, for instance adding in a weather-based Enrichment

But the challenge of context is not just to accrete as much context as possible - we also want to work to structure and schema the context we already have better. Currently Snowplow stores contextual information in our “fat” Redshift table using a simple namespacing approach. Rest assured that we are exploring cleaner ways of storing this information as part of our wider event grammar research!