Modeling events through entity snapshotting

At Snowplow we spend a lot of time thinking about how to model events. As businesses re-orient themselves around event streams under the Unified Log model, it becomes ever more important to properly model those event streams. After all: “garbage in” means “garbage out”: deriving business value from events is hugely dependent on modeling those events correctly in the first place.

Our focus at Snowplow has been on defining a semantic model for events: one that is built around the intrinsic properties found across all events. A semantic model helps to prevent business and technology assumptions from leaking into the event stream. This works to guard against outdated assumptions becoming “fossilized” in the event stream, and helps to make those streams significantly less brittle – and easier to evolve – over time.

We proposed an initial model for Snowplow events in our August 2013 blog post, Towards universal event analytics – building an event grammar. We have since discussed this approach with many interested parties, and have been pleased to follow other explorations of the topic, for example Carmen Madiros’ Lego Data Layer blog post series. I’ve also made heavy use of this proposed event grammar in my book, Unified Log Processing. The semantic approach seems to have resonated widely.

However, our thinking has evolved from our original event grammar proposal in one important aspect. During the 18 months elapsed since that blog post, we have been exposed to many more event streams defined by many more customers, and we have also had the chance to experiment with aspects of the event grammar through Snowplow’s own unstructured events, its custom contexts and more generally with our new Iglu project. What we have learnt from all this can be summed up like so:

An event is anything that we can observe occurring at a particular point in time. Each event is recorded as the set of relevant entities as they stood at that point in time

This statement may seem unrelated – perhaps even contradictory – to our original definition of an event grammar with six dedicated “slots” containing: Subject, Verb, Object, Indirect Object, Prepositional Object and Context. In fact, they are closely related and broadly complementary, and understanding the role of entities in events should allow us to derive a “version 2” of our event grammar which is significantly simpler and also more powerful.

In the rest of this blog post, we will cover the following:

- Introduce what we mean by entities

- Explore how entities change over time

- Review how our databases handle time

- Propose an approach based on entity snapshotting

- Revise our event grammar

- Represent our event grammar in JSON

- Draw some conclusions

1. Introducing entities

What is an entity? In event modeling terms, an entity is a thing or object which is somehow relevant to the event that we are observing. For example, in the sentence “I watched Gravity at my local theatre”, myself, the movie and the movie theatre are all entities:

We use the word “entity” because the word “object” is too loaded – it has too many connotations from Object-Oriented Programming (OOP), and it also has a separate grammatical meaning in terms of the “subject” of a verb versus the “object” of a verb.

Entities are everywhere in software. MySQL tables, backbone.js models, Protocol Buffers, JSONs, Plain Old Java Objects, XML documents, Haskell records – as programmers we spend an inordinate amount of time working with the entities that matter to our systems. It is no coincidence that these entities play a huge role in the events which occur in and around our software too.

There is a lot of confusion around the role of entities within events – even to the extent of one analytics company arguing that entity data is completely distinct from event data. In fact nothing could be further from the truth – as we’ll soon see, our events consist of almost nothing but entities. But before we look at the event-entity relationship, we need to understand how entities interact with time.

2. Entities and time

All objects exist in a moment of time

Amy Tan, The Bonesetter’s Daughter

In the real world as in software, entities change over time. If we can view our entities as consisting of properties, we can divide these properties into three approximate buckets:

- Permanent or static properties – properties that don’t change over the lifetime of the entity. For example, my first language

- Infrequently changing properties – properties that change infrequently, for instance my email address

- Frequently changing properties – properties that frequently change. For example, my geographical location

The exact taxonomy is not set in stone – for example, a person’s height will start as a frequently changing property, become a static property in adulthood, and then switch to an infrequently changing property as she grows older. Nor do these properties necessarily change in particularly directional or meaningful ways over time: my geographical location has patterns in it (such as my daily commute), but there’s no overarching trend across all the data.

Let’s imagine that Jack is playing a mobile game, and saving his progress as he goes. Jack is an entity, and the mobile game is another entity. Across three distinct save game events, Jack’s internal properties change:

To put it another way: it was a slightly different Jack who saved his game each time. If we want to analyze and understand these save game events, being able to review the “version of Jack” who enacted each event could be hugely important. How can we do this?

3. Time and databases

What matters in life is not what happens to you but what you remember and how you remember it

Gabriel García Márquez

We are surrounded by software that helps us to model entities in one form or another. Separately, we’ve learnt that the entities we care about change over time. Presumably all of this entity-modeling software makes it easy to record how our entities are slowly (or rapidly) changing over time? Actually, most of it does not.

Most systems that represent entities – databases, schema languages, serialization protocols and so on – have no concept of time as a dimension. These systems most often simply track the current state of each entity: accordingly as developers we are expected to update in place the existing data when some property changes. If Jack’s email address changes, then we must update the existing email address value in his record in the players table. In many systems, it is as if Jack’s email address was always the new one.

This isn’t such a

problem for permanent or static properties like Jack’s first language – but it’s a real pain for properties that change infrequently or frequently, such as his email address or location. Various software approaches have emerged to tackle this problem:

- Value versioning. In the HBase database, a cell (a.k.a. a value) is specified by a {row, column, version} tuple. You can configure HBase to store hundreds of versions of a column. By default the most recent version is returned, but you can also retrieve the value at a specific timestamp or between two timestamps

- Fact databases. The Datomic database stores “datoms” or facts consisting of an entity, attribute, value and “transaction” (i.e. time). These datoms are immutable facts – they are never updated, but new ones can be appended. You can query the database at a point in time or across a time window

- Periodic snapshots. In data warehousing, an ETL process can regularly (e.g. daily) capture the entity data from a transactional database at a moment in time, and store it in fact tables in the data warehouse

- Log triggers. A log or history trigger is set up in a database to automatically record all C/U/D (Create, Update, Delete) events on a given table

- Event sourcing. Where all changes to application state are stored as an append-only sequence of immutable events: we stop worrying about state and start worrying about state transitions. If we need an entity’s current state, then we can calculate it from the relevant event sequence

Each of these approaches to Change Data Capture has different pros and cons. And more importantly, many companies won’t have any Change Data Capture in place. So how do we make sure that we can cross-reference our events against the relevant entities as they existed at the time of the event?

4. Entity snapshotting

Storage is cheap and getting cheaper. Networks are getting faster all the time. If we care about the entities relevant to a given event, why don’t we just interrogate their state at the exact moment of the event and record these entities’ state as part of our event? To put it another way: let’s snapshot our entities’ state inside of our events, and thus record Jack’s exact properties each time he saved his mobile game.

There are some distinct advantages to this approach:

- It’s very simple to apply at event capture stage: interested in an entity? Attach it to your event

- There’s no need for Engineering to implement any kind of Change Data Capture in our underlying atemporal data systems

- At analysis time, there’s no need to cross-reference an entity’s state at the event time – it’s already attached

If we squint a little bit, we can see Snowplow’s existing support for “custom contexts” as a form of entity snapshotting. Let’s take this example from the JavaScript Tracker technical documentation:

window.snowplow_name_here('trackPageView', null , [{ schema: "iglu:com.example_company/page/jsonschema/1-2-1", data: { pageType: 'test', lastUpdated: new Date(2014,1,26) } }, { schema: "iglu:com.example_company/user/jsonschema/2-0-0", data: { userType: 'tester', } }]);Leaving aside the language of “custom contexts”, what we are doing here is recording the state of two entities – our web page and our user – at the exact moment of our page view event. These are entity snapshots in all but name.

In the next section, we will reconcile this new idea of entity snapshots with our earlier event grammar.

5. A revised event grammar

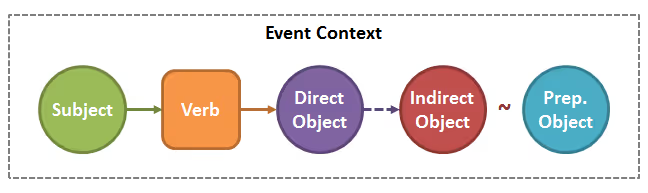

Back in the 2013 blog post, we identified six discrete building blocks from human language which would make up the semantic structure of our events. We introduced them with this diagram:

We explained the six building blocks thus:

- Subject, or noun in the nominative case. This is the entity which is carrying out the action: “I wrote a letter”

- Verb, this describes the action being done by the Subject: “I wrote a letter”

- Direct Object, or simply Object or noun in the accusative case. This is the entity to which the action is being done: “I wrote a letter”

- Indirect Object, or noun in the dative case. A slightly more tricky concept: this is the entity indirectly affected by the action: “I sent the letter to Tom”

- Prepositional Object. An object introduced by a preposition (in, for, of etc), but not the direct or indirect object: “I put the letter in an envelope”. In a language such as German, prepositional objects will be found in the accusative, dative or genitive case depending on the preposition used

- Context. Not a grammatical term, but we will use context to describe the phrases of time, manner, place and so on which provide additional information about the action being performed: “I posted the letter on Tuesday from Boston”

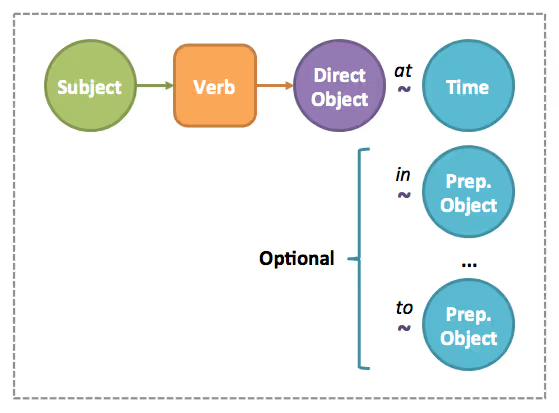

Knowing what we now know about entities, we can make two simplifications to this model:

- An Indirect Object is just a type of Prepositional Object. There’s no need to keep indirect objects as a separate concept

- Context is also composed of Prepositional Objects. For example, a time phrase has Preposition at and Object time</em>; a phrase of place has Preposition in or on or outside and Object location

Making these changes results in events that take this form:

- A requi

red Subject – a snapshot of the entity carrying out the action - A required Verb – the action being done by the Subject

- A required Prepositional Object – the time at which the event was carried out

- A required Direct Object – a snapshot of the entity to which the action is being done

- A set of optional Prepositional Objects – again consisting of entity snapshots

This updated event grammar is set out in this diagram:

As we predicted at the start of this blog post: our events now consist of almost nothing but entities. Apart from our Verb, our event consists only of entity snapshots, each tagged with the grammatical term that relates it to the rest of the event.

6. Our event grammar in JSON

So far this is all a little theoretical. At Snowplow most of our applied event modeling is done in Iglu-compatible self-describing JSON, so why don’t we sketch out what our revised event grammar could look like in this format?

Imagine that we are trying to model an in-game event where a player (Jack, perhaps) sells some armour to another player. In the following self-describing JSON, we represent this event as a set of annotated entity snapshots:

{ "schema": "iglu:com.snowplowanalytics.snowplow/event_grammar/jsonschema/1-0-0", "data": { "subject": { "schema": "iglu:de.acme/player/jsonschema/1-0-0", "data": { "playerId": "1213", "emailAddress": "l33t@gamer.net", "highScore": 220412 } }, "verb": "sell", "directObject": { "schema": "iglu:de.acme/armor/jsonschema/1-0-0", "data": { "type": "titanium", "condition": 0.63 } }, "at": { "schema": "iglu:com.snowplowanalytics.snowplow/time/jsonschema/1-0-0", "data": { "collectorTstamp": "2015-01-17T18:23:05+00:00", "deviceTstamp": "2015-01-17T18:23:02+00:00" } }, "prepositionalObjects": { "to": { "schema": "iglu:de.acme/player/jsonschema/1-0-0", "data": { "playerId": "7684", "emailAddress": "karl@gmx.de", "highScore": 220412 } }, "for": { "schema": "iglu:de.acme/price/jsonschema/1-0-0", "data": { "amount": "30", "currency": "doubloons" } }, "in": { "schema": "iglu:de.acme/level/jsonschema/1-0-0", "data": { "world": "Aquatic", "levelName": "Pirate Bay" } } } } }Note that all of the schema URIs are illustratory – don’t go looking for the underlying schemas in Iglu Central! There are a few things about this approach which stand out:

- The structure is very simple: there are some grammatical annotation

s like “directObject” and “at” but fundamentally we are just reporting on the state of various entities at a point in time - There are no limitations on the number or types of entities which can be added to the event

- All of our entities are well-structured, with Iglu schema URIs attached. These entities originate in the game’s own data structures, so it should be possible to convert these structures to JSON Schema and upload them into Iglu

This is a good place to pause and take stock. I’ve attempted to move the foundational Snowplow event grammar concepts forward by re-framing them in terms of entity snapshotting, a powerful approach which we are de facto already implementing via Snowplow custom contexts. I look forward to getting the Snowplow community’s thoughts and responses on the above – with the aim of evolving these ideas still further. Do please leave any and all comments in the Feedback section below!

7. Conclusions

- Entities and events are deeply intertwined concepts – we cannot understand an event without understanding the entities which were involved in that event

- Entities change over time, because they contain frequently and infrequently changing properties

- Most of the data systems we work with are atemporal. Change Data Capture is a methodology dedicated to trying to map entities’ state transitions in these atemporal systems over time

- Entity snapshotting gives us a simple but effective way of recording the state of our relevant entities at the specific moment of an event

- Our revised event grammar consists only of a verb plus various required and optional entity snapshots

- We can represent our event grammar using self-describing JSON. The model in JSON seems simple yet flexible

- We are looking forward to feedback on our re-framed event grammar leveraging entity snapshotting

Learn more about our unique approach to data delivery with a Snowplow demo.